Elgin History Museum, Compiled from the work of E. C. Alft and Barbara Schock

Although Elgin is shut down now with individuals asked to quarantine themselves, this is not the first time. In the 19th century, there were frequent epidemics that came with suffering and sorrow. In 1845, the ague – or “bilious fever” – raged. Many settlers fled town and nearly every remaining resident was prostrate. It was said that one man whose wife succumbed from the illness had difficulty finding assistance to bury her in a decent manner.

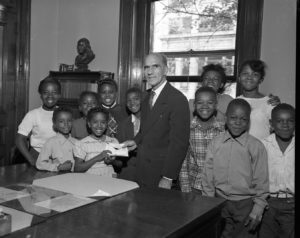

“Children have been swept away as with a pestilence,” reported the weekly Elgin Gazette in 1862-1863. This was right after former slaves, called “contraband,” arrived in Elgin. They traveled for two days in unheated boxcars after living in a crowded refugee camp. 16 African American children died mainly of smallpox. An equal number of white children died of scarlet fever and diphtheria. Different diseases, but the blame fell on the new war refugees.

Cholera hit the city in 1854, killing Elgin founder James Gifford, Cholera hit again in 1866. Diphtheria was an all-too-frequent visitor in the fall and winter months. Lottie Magden, 13, died on Saturday. Her brother, Eddie, 3, and her sister Lizzie, 15, died the following Wednesday. All three children were among several Elgin victims of diphtheria outbreak of 1883. The source of the disease was believed at the time to be a stagnant and slime-covered slough at the intersection of Dundee Avenue and Gifford and Summit streets. The bed of the wetlands was at the same level as neighborhood wells. A severe onslaught of diphtheria occurred in 1895, 1896, and 1897, when there were 42 deaths.

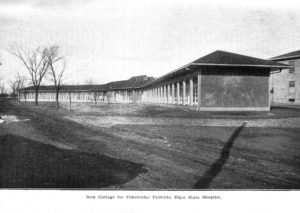

A slow moving epidemic, tuberculosis affected world populations from the 1600s through the 19th century. At the Elgin State Hospital in 1906, over 25 percent of all hospital deaths were caused by tuberculosis, including three doctors. To control the spread of the disease, a tent hospital was set up to isolate TB patients who were also patients at the state hospital. Within a few years, the care of TB patients was located in a specially built separate building, and not on the main wards. For the general Elgin population, private sanitariums took on the care of tuberculosis patients.

A slow moving epidemic, tuberculosis affected world populations from the 1600s through the 19th century. At the Elgin State Hospital in 1906, over 25 percent of all hospital deaths were caused by tuberculosis, including three doctors. To control the spread of the disease, a tent hospital was set up to isolate TB patients who were also patients at the state hospital. Within a few years, the care of TB patients was located in a specially built separate building, and not on the main wards. For the general Elgin population, private sanitariums took on the care of tuberculosis patients.

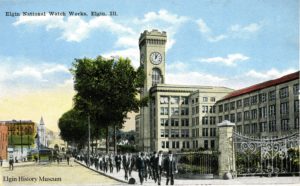

July 1916 was the hottest month Elgin had known up to that time. Typhoid fever killed one person on July 5, but eight others in the city were ill with the disease. Many of the sick were Elgin National Watch Company employees. Smallpox was also reported. Quarantine signs were posted outside of homes with sickness warning neighbors not to visit and milkmen to not pick up empty bottles. Typhoid fever is a bacterial infection picked up through contaminated water, milk, shellfish, and other foods. It causes headache, fever, sore throat and diarrhea. Diagnosing typhoid is difficult in the early stages because the symptoms are common for many diseases.

Dr. Alban Mann was the City of Elgin physician and kept records of the typhoid cases. He tested the city water supply and found no typhoid, the same with the milk supply. By August 16, there were at least 25 cases, but officials could not find the source. Esther Range, who worked in the Spring Room at the watch factory, died. The next day there were 10 more cases. The third victim, Verna Brandow, died on August 18. She was employed in the Stem Wind department at the factory.

Dr. Alban Mann was the City of Elgin physician and kept records of the typhoid cases. He tested the city water supply and found no typhoid, the same with the milk supply. By August 16, there were at least 25 cases, but officials could not find the source. Esther Range, who worked in the Spring Room at the watch factory, died. The next day there were 10 more cases. The third victim, Verna Brandow, died on August 18. She was employed in the Stem Wind department at the factory.

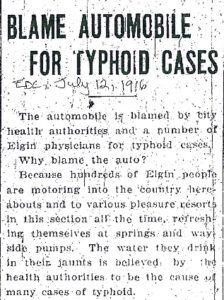

There were all kinds of ideas on what was causing the disease. Some residents thought it was the public bathing beaches on the Fox River, or sediment in the city drinking water, or pollutants from new automobiles. In the end, over 200 residents were stricken, with 26 deaths reported that year. The last person to die of complications of typhoid fever on December 12, 1916 was Elizabeth Simms, who had been ill for 14 weeks. She worked 30 years in the Stem Wind department of the factory. The source of the contamination was traced by Dr. Mann to a leaky valve, which separated water from the watch factory’s reservoir on Watch Street and water taken from the river. The leaky valve allowed river water seepage to contaminate water pumped to drinking fountains throughout the watch factory building. The watch factory instituted mandatory vaccinations for typhoid. The vaccine was to be given in a series of three injections over a period of about three weeks. It was said that women and men had fainted during the process. There were also rumors that some workers had to be taken to the hospital after they received the treatment. The company had a history of demanding vaccinations. In 1882, 34 years before the typhoid epidemic, all employees were vaccinated for smallpox.

There were all kinds of ideas on what was causing the disease. Some residents thought it was the public bathing beaches on the Fox River, or sediment in the city drinking water, or pollutants from new automobiles. In the end, over 200 residents were stricken, with 26 deaths reported that year. The last person to die of complications of typhoid fever on December 12, 1916 was Elizabeth Simms, who had been ill for 14 weeks. She worked 30 years in the Stem Wind department of the factory. The source of the contamination was traced by Dr. Mann to a leaky valve, which separated water from the watch factory’s reservoir on Watch Street and water taken from the river. The leaky valve allowed river water seepage to contaminate water pumped to drinking fountains throughout the watch factory building. The watch factory instituted mandatory vaccinations for typhoid. The vaccine was to be given in a series of three injections over a period of about three weeks. It was said that women and men had fainted during the process. There were also rumors that some workers had to be taken to the hospital after they received the treatment. The company had a history of demanding vaccinations. In 1882, 34 years before the typhoid epidemic, all employees were vaccinated for smallpox.

The great influenza pandemic of 1918, which caused an estimated 20 million deaths in Europe and the Americas, was the last major scourge to inflict the city. Although 70 died in Elgin, the outbreak here was relatively mild compared to 236 dead in Joliet and 125 in Aurora. Also in 1918, Elgin experienced a smallpox epidemic started by a young girl who traveled from Jacksonville to visit her married sister. The sister’s husband was a barber who worked the first two days after he was infected. There was an immediate 20-day quarantine to suppress the disease and an immediate large-scale vaccination program. Over 5,000 vaccinations were given to Elgin citizens, but many refused to cooperate. 117 cases of smallpox were reported, but fortunately, no deaths.

Later in the 20th century, Elgin had cases of polio and AIDS. Both diseases were rampant for periods of time with unknown sources and cures. Medical scientists, public health workers, and improved sanitation have eliminated the fears of an earlier day, but the coronavirus is a reminder that the battle against contagious disease is not yet won.