‘Significant Black Women of the Reconstruction Era and Beyond’ with Dr. Felicia LaBoy

This presentation took place on Sunday, February 20th, 2022. The event was not recorded because of technical difficulty, but gratefully, Phil Broxham of Grindstone Productions was there and he took […]

Rachmaninoff in Elgin

Researched and written by Richard Renner Rachmaninoff’s appearance in Elgin came in the midst of a tour which had started in Detroit on October 12 and had included stops in […]

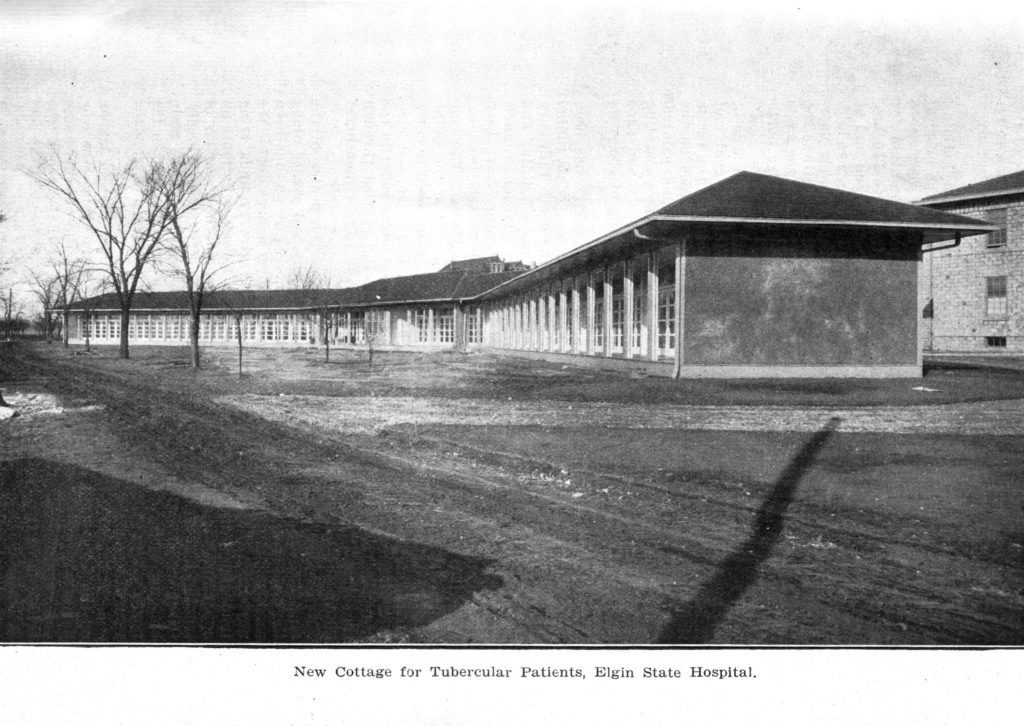

Elgin Epidemics

Elgin History Museum, Compiled from the work of E. C. Alft and Barbara Schock Although Elgin is shut down now with individuals asked to quarantine themselves, this is not the […]

443 W. Chicago Street

The snow is gone and the sun is out – it’s a great day for a walk! This week’s house was inspired by the Near West neighborhood and the new […]

117 Tennyson Court

Happy Good Friday, Elgin! There is this tiny street in the Elgin Historic District called Tennyson Court that I just love. The homes on this street are all very neat […]

571 Center Street

For this week’s house, I wanted to feature a house owned by a doctor or nurse as a tribute to all the hospital staffers working around the clock during this […]

The Hubbard Families of Elgin: Part 2

By David Siegenthaler In 1866-67, William G. Hubbard’s second Elgin home, a large Italianate, was built at 378 Division St. In November 1873 this home was sold to Emeline Borden, […]

406 Prospect

This week’s house came about because I was looking for a DIFFERENT address on Prospect Street – and this one caught my eye as well. 406 Prospect Street was built […]

443 E. Chicago Street

I was recently introduced to The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) (Link to the website in comments below) from an email the Gifford Park Association sent to its members. This email also […]

703 Raymond Street

Happy Friday! Who likes brick houses? 703 Raymond Street is a beauty. This home is associated with Paul Kemler Sr., a prominent resident of Elgin’s history. In 1889, he built […]